CAPTAIN G. K. ROSE, M.C, DESCRIBES LIFE IN THE TRENCHES DURING THE GREAT WAR, AS A MEMBER OF OXFORDSHIRE AND BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INANTRY

From The Story of the 2/4th Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, by Captain G. K. Rose M.C. (Oxford: B.H. Blackwell, 1920)

So far I have said little of the hardships suffered by the Infantry. Indeed, in places I have laughed at them. Those scenes and experiences which marked a soldier’s life in the front line will have been supplied by those who knew them as familiar background to my story. But I grudge leaving them to the imagination of civilian and non-combatant readers. I seriously doubt whether the average man or woman has the least inkling of what really happened ‘out there.’ Talk over-heard or stories listened to may in special instances have revealed a fragment of the truth. For most people the lack of real perception was filled in by a set of catchwords. As the war dragged on, the civilian mind of England passed into a conventional acceptance of phrases habitually read but improperly understood, until the words ‘raids,’ ‘barrages,’ ‘objective,’ ‘craters,’ ‘counter-attack,’ ‘consolidation,’ became tolerated as everyday commonplaces. Take a war-despatch of 1916 or 1917–it is made up of a series of catch words and symbols. Plenty of our famous men, I am sure, who went to the front and perhaps wrote books afterwards, on arrival there made remarks no less foolish (and excusable) than the old lady’s ‘nasty slippery place’ where Nelson fell. The Somme and Ypres battlefields are inconceivable by anyone who has seen nothing but the normal surface of the earth. The destruction of towns, villages and farms is without parallel in history or fiction. To witness some scenes in the Retreat of 1918 was to stake one’s sanity. There are no standards by which civilians and non-combatants can appreciate the true facts of the war. Deliberate reproduction would hardly be believed. Suppose, for instance, this winter I were to dig a large hole in a field, a quarter fill it with liquid mud, and then invite four or five comrades, all arrayed in much warlike impedimenta, but lacking more extra covering than a waterproof sheet each, to the hole to spend two nights and a day in it–I should be credited with lunacy. Yet I should be offering a fair sample of front-line accommodation during the Great War.

Reliefs

Reliefs took place at night. Alike through snow or rain, or in a biting wind, the Infantry marched up from huts or ruined barns (its rest billets) to reach the line–a distance normally of seven miles. First by road, next by a slippery track, finally through a communication trench deep in mud, our soldiers had to carry each his rifle and 120 round of ammunition, a share of rations, gumboots, a leather jerkin and several extras–a load whose weight was fully 50 pounds. Many staggered and fell. All finished the journey smothered in dirt. Boots, puttees and even trousers were sometimes stripped from the men by the mere suction of the mud, in which it was not unusual to remain stuck for several hours. Men, though not of our Battalion, were even drowned. [Footnote 7: This fact, which will hardly be credited by future generations, is related from the actual knowledge of the writer.]

Parties were often shelled on the way up, or else were lost and wandered far. From Headquarters, reached about midnight, of the Company being relieved guides would take two platoons into the front line ‘posts,’ the other two to the positions in support.

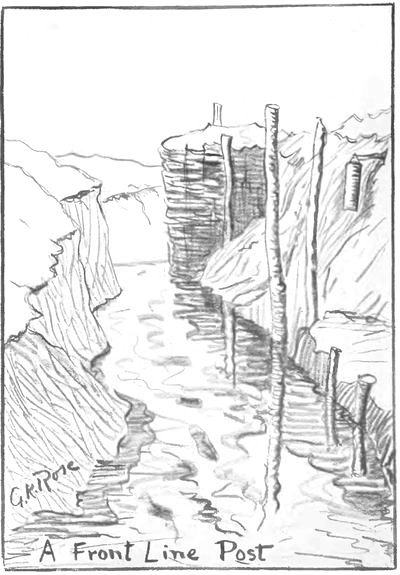

The Front Line

In the front line itself there was often no better shelter than an old tarpaulin or sheet of corrugated iron stretched across the trench. At some ‘posts’ there was nothing better to sit on than the muddy ‘fire-step’ or at best half a duckboard or an old bomb box. Despite continuous efforts to keep one dry place to stand, the floor was several inches deep in water and mud.

Movement in any direction, save for a few yards to the flanks if the mud had been cleared away or dammed up, in daylight was impossible. No visitors came by day. Stretcher bearers were not always near. A fire could not, or if it could, might not be lighted. Therefore no hot meal, except perhaps a little tea made over a ‘Tommy’s Cooker,’ was procurable by day.

The post would be shelled or trench-mortared at intervals. In earlier days it might be totally blown up by a mine, or in later times bombed or machine-gunned from the air. For 30 to 40 high explosive shells to fall all round a post was quite common. Sometimes a ‘dud’ would fall inside it, or a huge ‘Minnie,’ which burst in the wire, cover the occupants with earth and splinters. The crash of these huge trench-mortar bombs was satanic; and there was always a next one to be waited for. Sometimes whole posts were wiped out. If there were wounded they could expect no doctor’s help before night. Often by day, owing to mud and German snipers, it was impossible to lift a wounded man from where he had fallen.

Night, longer than day, was also worse. Pitch darkness, accompanied maybe by snow or mist, increased the strain. With luck the great compensation of hot food–tea and stew–would be brought up by the ration parties. But sometimes they were hit and were often lost and arrived several hours late. The sandbags containing a platoon’s rations for a day were liable to be dropped, and bread arrived soaked through or broken and mud-stained. Moreover, the darkness which permitted parties from behind to reach the post also decreed that the post should get about its work. Had the wire a weak place, the Germans knew of it, and directly the wiring party set about mending it lights were sent up, which fell in the wire close to our men, and machine-gun bullets banged through the air. Besides the wire the parapet required constant attention. At one place, where a member of the post had been killed by a sniper, it would want building up; at another, a shell perhaps had dropped only a yard short of the trench during the evening ‘strafe,’ the passage would be blocked and the post’s bomb-store buried. All this had to be put right before dawn. During the night a patrol would be ordered to go out. Men who were sentries by day or were the covering party for the wiring might be detailed for this. After that was over the same men took turns as sentries.

Sleep

Sleep was confined to what those not on duty could snatch, wrapped only in the extra covering of a waterproof sheet, in a sitting posture on the fire-step. At dawn, when the men at last could have slept heavily, came morning stand-to. This meant standing and shivering for an hour whilst it grew light and attempting to clean a mud-clogged rifle. Those Englishmen in England (and in France) who have slept warm in their beds throughout the war should remind themselves of those thousands of our soldiers who wet through, sleepless, fed on food which, served as it finally was up in the trenches, would hardly have tempted a dog, have stood watching rain-sodden darkness of night yield to dismal shell-bringing dawn, and have witnessed the monotonous routine of war till sun, earth, sky and all the elements of nature seemed pledged in one conspiracy of hardship.

In Support

What of the two platoons in ‘support’?

Their lot was preferable. They were placed about 400 yards behind the actual front and lived (if such existed) in deep mined dug-outs. Until the later stages of the war deep dug-outs, which were subterranean chambers about 25 feet below the level of the ground and nearly shell-proof, were made only by the Germans, whose industry in this respect was remarkable. Found and inhabited by us in captured territory, these dug-outs had the defect that their entrances ‘faced the wrong way,’ _i.e._, towards the German howitzers. Sometimes a shell, whose angle of descent coincided with the slope of the stairs, burst at the bottom of a dug-out, and then, of course, its occupants were killed. If no deep dug-outs were available, the support platoons lived in niches cut into the side of the trench and roofed over with corrugated iron, timber and sandbags. Such shelters afforded little protection against shelling.

In event of attack by the enemy it was the normal duty of support platoons to garrison a line of defence known as the ‘line of resistance.’ They might be ordered to make a counter-attack. When no fighting was taking place their work was likely to consist in carrying up rations and R.E. materials (wooden pickets, sandbags, coils of barbed wire, etc.) to the front line. This work had to be done at night, because in winter ‘communication trenches’ (which alone made daylight movement possible from place to place in the forward zone) were so choked with mud as to be impassable. The day was spent in ‘mud-slinging,’ _i.e._, digging out falls of earth from the trench, rebuilding dug-outs or laying fresh duckboards (wooden slats to walk on in the trenches). When the evening’s ‘carrying parties’ were finished, the men had some sleep, but support troops were often used as night patrols in No-Man’s-Land or as wiring parties.

Rotation of Platoons From Support, To the Front Line, To Being Relieved

After a day or longer in support they were sent up to relieve, _i.e._, exchange positions with, their comrades in the front line posts. Four days was the usual ‘tour’ for a company. During it each platoon did two spells of 24 hours in the posts and the same back in support. When the four days were over, a fresh company relieved that whose tour was finished. The one relieved moved back to better conditions, but would still be in trenches and dug-outs until the whole Battalion was relieved.

The English infantryman stands for all ages as the ensample of heroic patience, which words or cartoon fail utterly to convey.

The Experience of Front Line Officers

How did the Company Commander and his officers fare in the trenches?

The Platoon Officer shared every hardship with his 25 men. If there was a roofed-in hole with a box for a table he had it, for his messages were many. To the Company Commander a rough table was quite indispensable, and so were light and some protection from the rain. Without these essentials he could never have received nor sent his written instructions, consulted his maps nor spoken by telephone, on which he relied to get help from the artillery. The Company Sergeant-Major, a few signallers and some runners were his familiars, and he lived with and among these faithful men. Quite often the Company Commander’s dug-out was appreciably the best in the company area. Sometimes it was little better than the worst. In the spring of 1918 it was often only a hole.

Every good Company Commander made a point of visiting each night all his front line posts and spending some time with each, not only to give orders, direct the work and test the vigilance of the sentries, but in order to keep up the Company’s morale. The worse the weather or the shelling the higher that duty was. Likewise the Battalion Commander used to visit Company Headquarters once a day and every front line post at least once during a tour. The journey to the front line, possible only in darkness, was very dangerous. Shells were bound to fall at some point on the way, the enemy’s machine guns or ‘fixed rifles’ were trained on every probable approach, and the Captain in ordinary trench warfare was as liable to be killed as any Private. Responsibility, however, made these nightly walks not only necessary but almost desirable.